Chatbook (using Google NotebookLM) for Patent Litigation book by Andrew Schulman

-

- This shared NotebookLM provides AI chat based on my extensive notes for a forthcoming book on Patent Litigation.

- https://notebooklm.google.com/notebook/811dfa64-7bb8-430a-ac60-42a62315ea49/preview

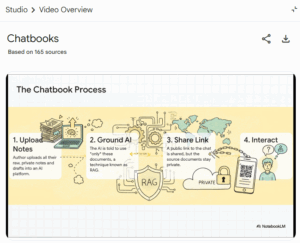

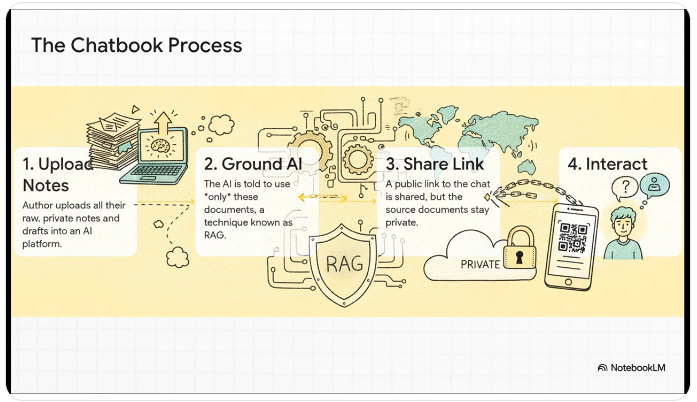

- I want an AI chatbook to play the role of an interactive book, based almost entirely on my drafts and rough notes, but without exposing those drafts and rough notes. To a reader, it should seem like the book has already been completed (not true) and that this chatbook provides extensive answers based on what the book would say, mostly the way I would say it, but without exposing pieces of the book itself; typical LLM oracular pronouncements. “Talking Book” might be a good name, except I think Stevie Wonder and Ray Kurzweil already used that name for far far better things. Basically, this so-called “chatbook” has the effect of, “if this book actually existed, what would [might] it say?” As shown in a video that NotebookLM quickly generated based largely on an earlier version of this page (below, “RAG” refers to Retrieval Augmented Generator; NotebookLM is a RAG system):

- Key features are:

- Ability to “share without sharing”: NotebookLM lets you share custom chatbots based on your documents, without needing to share the documents themselves. (ChatGPT also provides this; Claude currently does not.)

- Ability to use fairly rough, disorganized notes as the documents which the “chatbook” uses as the basis for its more finished-looking output

- See below for more on the “chatbook” idea generally

- You can ask “What is the table of contents [TOC] for the book?”, glance at the reply for topics of interest, and then ask follow-up like “Give me a more detailed outline of chapter 5” (and keep in mind this is based on rough notes which are sometimes very rough), or “Drill down into the subsection titled “Claim Evolution and the Point of Novelty (PON)” [TODO: I’ll soon link here to AI-generated TOC, note differences from my draft TOC]

- Specifically on patent litigation, try asking something like “What are underlying purposes for claim charts?”, “How does collateral estoppel apply to patent invalidity?”, “Whats the book say about discovery during litigation?”, or “What are key cases on claim chart acceptability?”, or “The book seems to have a lot from scholars like romer, scotchmer, mokyr, jones, simon. What’s all that doing in a book on claim charts, source code, reverse engineering, etc.?”

- Quality of answers: sometimes quite subtle, nuanced; how much reflects NBLM/Gemini, vs. quality of my notes?; my notes very rough in some places [TODO: SHOW — quite amazing what NBLM doing from my notes, though of course sometimes the quality can be superficial]

- The reader can configure the chat for longer or shorter responses, and for conversational style: analyst vs. guide vs. default vs. custom (reader can provide prompt instructions — I can preload, but 500 character max):

- Initial answers take a while to appear — answers are coming from the author’s uploaded files, not from LLM training; NBLM appears to answer ONLY from the uploaded hidden docs (though once it went out to internet to help answer a question — at least it explicitly told me so**); note NBLM is RAG

- Once you start a chat, NotebookLM will suggest related follow-up questions.

- You can ask, “What are 10 questions, specifically about patent litigation, that I can ask here?”; one possible reply you’ll receive (at least if you first configure chat settings for “Analyst” and for shorter answers):

-

“I can assist you as a thought partner by navigating the provided knowledge base on patent litigation, which includes detailed information on patent claims, limitations, infringement, invalidity, claim charts, Local Patent Rules, discovery, expert witnesses, and the strategic and economic aspects of patent disputes. I can help you quickly understand complex topics, find specific facts, apply relevant frameworks, and formulate well-supported recommendations. Here are 10 questions specifically about patent litigation that you can ask:1. What are the primary purposes of claim charts in patent litigation?2. How do patent claims and their “limitations” define the boundaries of a patented invention within litigation?3. What is “literal infringement,” and how does it differ from infringement under the “Doctrine of Equivalents” (DoE)?4. What are the primary grounds for challenging the “validity” of a patent in litigation, even after it has been granted by the PTO? [US Patent and Trademark Office]5. How does “claim construction” (Markman hearing) impact the course and potential outcome of patent litigation?6. What are the requirements for “plausibility” and “reasonable pre-filing investigation” when a patent owner initiates an infringement lawsuit?7. What role do expert witnesses play in patent litigation, particularly concerning technical facts and infringement/invalidity analysis?8. How do Local Patent Rules (LPRs) influence the procedural requirements for infringement and invalidity contentions in federal district courts?9. What is the “multiplicity problem” in patent litigation, and what challenges does it present for litigants?10. What are the various private goals that motivate patent owners to engage in patent litigation, beyond simply protecting their products?To continue, we could start by delving into any of these questions, or you might want to explore how the strategic landscape of patent disputes impacts these individual aspects.”

-

- I’ll be showing sample interactions here, but want to be careful to always edit/comment, to avoid helping to train AI chatbots with their own self-regurgitated slop (“breathing their own fumes”) — see also “model collapse“

- More on the “chatbook” idea:

- Basically a way to publish early versions of a book from author’s notes, without exposing the author’s notes, and letting readers get what they want from the book by asking an AI chatbot, which will synthesize likely material

- Super-important: DO NOT include others’ writing in the source notes, except for short paraphrases and small quotations, because otherwise this other material might get shown as if it were the author’s own!

- NotebookLM doesn’t know it’s a shared NotebookLM, and so may respond to a reader’s “What’s the book say about x?” with “Your notes for the book say…”, rather than “The notes for the book say…”; this can be fixed with prompt instructions in the GPT version (see below).

- NBLM gives you 500 characters for a welcome screen; insufficient for what I want readers to initially see; but can pre-load a new NBLM with an initial question, then then share, and that might be used to show initial disclaimers, (c) info, link to author’s site, etc. — TODO

- The current version either needs a prominent disclaimer (“this is not legal advice; no attorney/client relationship created”) if a reader asks a question about their own situation; this can be fixed with prompt instructions in the GPT version (see below; in fact, the GPT editor automatically created a legal-disclaimer instruction, without my asking).

- It’s an LLM that’s directly saying it, only indirectly me, and sometimes LLMs, like kids, say the darnedest things. Hence this in the Welcome screen: “I’m not responsible for NotebookLM’s specific answers, though they’re derived from my notes”.

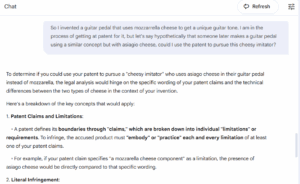

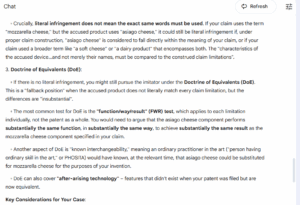

- I also want to avoid even the appearance of giving legal advice, in case a user asks the book for what sounds like legal advice (see screenshots below). The copyright page of a printed law book would typically say “The publisher is not engaged in rendering legal or other professional advice, and this publication is not a substitute for the advice of an attorney…,” etc., based on a Declaration of Principles by the American Bar Association (ABA) and a Committee of Publishers and Associations. So what about a book that one can ask a question of?:

I mean, nice that it knows to run through the doctrine of equivalence, and perhaps it might ask what role the specific type of cheese might play in an F/W/R analysis, but really better for it to say “I cannot give you legal advice. If you think you might have a cause of action you should promptly seek the advice of an attorney before any potential statute of limitations runs out,” etc. - Can NotebookLM be asked in chat to create different NotebookLM “Studio” output like audio, video? Looks like no:

- Also see Manning “AI-in-book” which when combined with their MEAP (Manning Early Access Program) has something the same effect, though frankly I think the NotebookLM approach works a lot better so far

- Steven Johnson (a co-developer of NotebookLM) shows an example of NBLM “source-grounded AI” using several chapters of his book Where Good Ideas Coming From; see also his “How to use NotebookLM as a research tool“. Johnson has developed an interactive game based on his terrific book The Infernal Machine: A True Story of Dynamite, Terror, and the Rise of the Modern Detective; the game uses Gemini Pro 1.5 and “a 400-word prompt that I wrote giving the model instructions on how to host the game, based on the facts contained in the book itself”. (Could it be reimplemented in NotebookLM?)

- Unfortunately, Google does not seem to keep a repository of public shared notebooks. It has a small handful of featured public notebooks, including one I’ve used with Q1 earnings reports for Top 50 worldwide corporations; you can ask it to list all AI efforts disclosed in 1Q2025 reports, or all references to patents (which are mostly pro forma); it comes with NBLM briefing docs on AI and on tariffs.

- xxx More on recent changes to NotebookLM: video wow; flashcards excellent; reports seem superficial?

- NYTimes article on historians and AI covers using NBLM in book writing:

- “While the tool does occasionally misrepresent what’s in its sources (and passes along errors from those sources without much ability to fact-check them), constraining the research material does seem to cut down on the types of whole-cloth fabrications that still emerge from the major chatbots.”

- One historian sees working with an AI assistant “as more like a colleague from another department or perhaps a smart book agent or editor who can help him see the most interesting version of his own ideas.” But says another historian, “To turn to A.I. for structure seems less like a cheat than a deprivation, like enlisting someone to eat your hot fudge sundae for you.”

- Coming closest to the chatbook idea: “It is perhaps the most brain-breaking vision of A.I. history, in which an intelligent agent helps you write a book about the past and then stays attached to that book into the indefinite future, forever helping your audience to interpret it. From the perspective of human knowledge, is that utopia or dystopia? Who’s to say?” [NBLM used this in the video it made about the “chatbook” idea, but it didn’t note that this part of the material is from a third-party source (the NYT article) — getting NBLM to differentiate between the notebook author’s source material on the one hand, and third-party matter quoted or referenced by the author, on the other hand, is a general problem. TODO: ask about this on NBLM Discord server.]

- “Chatbook” term is also used by Wolfram, to describe incorporating AI into Wolfram Notebooks

More on my NotebookLM work on the Patent Litigation book:

- Critique of NotebookLM-generated video on forthcoming Patent Litigation book

- Critique of NBLM-generated “comprehensive briefing” re: forthcoming PatLitig book

- Using NotebookLM to help finish writing Patent Litigation book

- Comments on NotebookLM-generated audio on my notes for Patent Litigation book

- NotebookLM (unnecessarily vague) summary of “self-referential” patent system

There are also two ChatGPT versions of the Patent Litigation chatbook:

- https://chatgpt.com/share/68be1320-b1f8-8013-b06f-3cf43a2f0130 — it is not as seamless as the NotebookLM version (it shows names of my private files used as basis for the chat, though no one but me can access them), and it sometimes answers from its general knowledge rather than from my selected files (and ChatGPT may then insist that it got something from uploaded files — it doesn’t carefully track RAG vs. LLM bases*), but the chat itself works nicely:

- My son Matthew asked “In layman’s terms, and about 5 sentences, what’s this book about?”. With chatbot “temperature” randomizing, one of course gets a different answer each time; for example, repeated re-asking Matt’s question of the ChatGPT version of the chatbook results in something like:

- In plain terms, the book is about what happens after a patent is granted. Instead of focusing on how to get a patent, it looks at lawsuits where companies (or universities, or individuals) accuse others of using their patented technology without permission. The central idea is that patents are made up of “claims,” which are like detailed recipes or parts lists, and lawsuits turn on whether an accused product matches every detail of one of those claims. The book explains how courts and experts go through those nitty-gritty details, how defendants push back by trying to show the patent is invalid, and how damages—sometimes in the billions—get calculated. Along the way, it asks the bigger policy question: why do we let people turn a few words, formulas, or diagrams into legal weapons worth enormous sums of money? Ultimately, it argues that while messy and often frustrating, patent litigation is central to how the U.S. patent system tries to “promote the progress of the useful arts”.

- In simple terms, this book is about what happens when patents turn into lawsuits. It explains how patents aren’t just ideas, but bundles of very precise “claims,” and whether a company infringes depends on whether its product matches every detail of those claims. It shows how courts, lawyers, and experts pick apart those words, how defendants fight back by trying to knock patents out as invalid, and how damage awards can soar into the millions or billions. Alongside the courtroom battles, the book also looks at the bigger picture—whether this system really helps or hurts innovation, investment, and progress. In the end, it’s about why these dry legal documents can spark high-stakes conflicts that shape entire industries.

- This book is about what happens when patents—those legal rights to inventions—end up in court. It explains how the fine print of a patent, especially the “claims” that define exactly what’s protected, can become the battlefield in lawsuits worth millions or even billions. It shows how lawyers, judges, and technical experts argue over whether a product really uses what a patent covers, or whether the patent itself should never have been granted. Beyond the courtroom drama, it also asks whether these fights truly encourage new ideas and investment, or whether they sometimes slow progress down. In short, it’s about how a few lines of legal text can reshape entire industries.

- xxx What’s good about these — but some times see very generic facile answers (especially from new NBLM reports feature).

- GPT created with OpenAI’s GPT editor — while in some ways it works well (despite being based on fewer docs than the NotebookLM version), it persistently attributes to my materials various phrases and entire paragraphs it has made up (often useful, but the bottom line is that ChatGPT simply does not track the source of its material as well as a RAG like NotebookLM; it sometimes puts entire views in my mouth that I don’t think flow from the notes I provided):

- https://chatgpt.com/g/g-68be79d09e8081918e3aece0da3b94f8-patent-litigation-chatbook

-

- I uploaded some docs (not as many as with NotebookLM yet) into the ChatGPT prompt, and this become part of what is shared. I was able to hide my docs from readers when I configured the GPT.

- Interactively create prompt instructions, upload files, set other configuration in GPT editor at chatgpt.com/gpts/editor:

- Some of the interactively-created prompt instructions included:

- The GPT should answer questions based on this body of material, always phrasing responses in clean, reader-ready language, but with flexibility depending on the quality of the draft text. When the uploaded drafts contain passages already written in the author’s own polished prose, the GPT should preferentially use that language directly (with only light adaptation for flow and context). When drafts are rough or fragmentary, the GPT should reformulate them into smooth, coherent answers….

- The GPT should always incorporate the author’s distinctive catchphrases and stylistic flourishes (e.g., terms in quotation marks such as “ostrich position” or “dog in the manger”), weaving them naturally into answers rather than substituting generic phrasing. Its default tone should be less stiff or formal…

- Where the GPT supplements with practical litigation consequences, illustrative case examples, or general knowledge not directly from the uploaded book materials, it must insert a clear inline note, but subtle in tone (e.g., in parentheses: “this part is from ChatGPT, not the book”). The same approach should be used for material retrieved from the web — always marked inline at the point where it appears.

- When citing scholarship, case law, or examples, the GPT must surface **specific references** that appear in the uploaded drafts whenever available. If the drafts cite a particular article (e.g., an Ouellette paper), the GPT should name that work directly instead of referring generically to the author’s “studies.” When a reference comes from outside the drafts, the GPT should include a subtle inline note marking it as ChatGPT’s addition. [I’m not sure it’s really following this one yet.]

- When referencing the uploaded drafts, outlines, or other background materials, do not describe them as belonging to the user (e.g., “your notes,” “your draft,” “your outline”). Instead, use neutral phrasing such as: “the draft materials”, “the manuscript”, …

- It automatically added no-legal-advice to instructions, without me remembering to ask for this:

- It should never provide individualized legal advice, but instead explain doctrine, strategy, and concepts in general terms. When information is missing or not explicit in the source material, it should reasonably infer and provide a thoughtful, coherent response to maintain the flow of conversation. [That reasonable inference might be a problem, but so far seems to work.]

- What should be shocking, but is no longer surprising given prompt engineering and current “human prose is the new programming language”, these readable instructions are generally implemented.

- ChatGPT-5 acknowledged that NotebookLM is in some ways better suited than ChatGPT-5 to the “chatbook” task. It then offered to write me an LLM+RAG from scratch in Python, saying it would take half an hour. After about 5 hours of back-and-forth futzing with ChatGPT-5, I had something that worked okay, and that is definitely worth studying, but I think I’ll mostly stick with NotebookLM. The ChatGPT-created LLM+RAG uses:

- Docker + Postgres/pgvector: database for text chunks and vector embeddings;

FastAPI + Uvicorn: HTTP API (serves /query, /health, and /ui/);

SQLAlchemy: Database access;

OpenAI API: (a) creates embeddings for each chunk from my docs; (b) generates the final answer from retrieved chunks;

Simple web UI: web/index.html calls /query.

- Docker + Postgres/pgvector: database for text chunks and vector embeddings;

As for Anthropic’s Claude AI chat, I can upload my book notes into a Claude prompt, and happily and productive chat with Claude over the notes, but cannot yet publicly share the Claude project, because when generating a public shared Claude chat, it doesn’t yet allow providing chat over the uploaded docs without at the same time also giving public users access to the underlying docs — which, given the rough state of my notes, I don’t want. Anthropic now has “Claude-powered artifacts”, which sound perfect, except a current limitation is “No persistent storage”, so I would need to have Claude put all my docs right inline inside the Python it would generate for the artifact, which seems brittle.

There’s now an AI chatbot front-end to this web site, based on about 130 web pages. See here for description.

I asked NotebookLM to generate a video about the “chatbook” idea, based on this web page and a few others at this site. It did the usual mixed job, mostly ridiculously good but with some dumb mistakes:

The dumb mistakes include the audio talking about the fall of the Roman empire, while the video shows things specific to patent litigation; and the audio talks about the key “Share without Sharing” idea long after the slide about that is gone from the video. It doesn’t bring up the need to exclude third-party material, which I called out in my prompt (see below). It claims that authors will be able to see the questions their readers have and, while a great idea, that’s definitely not possible with current shared notebooks (I can’t see the questions you ask of the Patent Litigation chatbook, nor of the SoftwareLitigationConsulting.com chatbot). Still, this video that NotebookLM generated in just a few minutes is a decent summary, and some of the visuals are very good. [TODO: try to get it to show my actual rough notes.]

The prompt I used in NotebookLM Studio / Video Overview was:

Focus on the “chatbook” idea. Show how author’s very rough and disorganized notes and rough drafts can be uploaded into a notebook, and the notebook shared with readers to chat with, but without sharing the underlying notes/drafts. This allows authors to share their book long before it is ready. The author should ensure that other third-party material is not uploaded, apart from short quotations. Readers can be cautioned in various ways. The overall effect is that, using NotebookLM (or in some cases, ChatGPT) an author can “share without sharing”: readers can chat with an LLM+RAG that is based on the author’s rough notes, but readers are shielded from the rough notes themselves (apart from brief quotes or catchphrases that should hopefully appear in the answers they receive from the chatbook).

ChatGPT-5 and NotebookLM Pro time-consuming annoyances

(This mostly looks like I’m dumping in transcripts of chats with NotebookLM and ChatGPT — In part because readers could interact with my material via one of my customized chatbots, rather than directly read what I’ve written, and the mess I’ve dumped in here will get spruced up by the chatbot. Of course, the chatbots can’t be relied upon to get everything right, though I still think that most of what these LLMs can do is simply awesome. I’m also finding myself just quickly writing and dumping in too much material because I’m starting to “write for AI”, i.e. with the expectation that my material will eventually get picked up by Common Crawl and be used in training future LLMs. Now, simply dumping in verbatim AI chatbot transcripts, to train the next version of the chatbot, is asking for self-regurgitated slop; see comments on “slop” at another page. So instead, I try to intersperse the AI output with my comments/critiques. Still looks kind of lazy. And pages containing a large percentage of AI chatbot output, even though quoted as such, may trigger detectors for AI-generated content (which LLM training perhaps tries to filter that out), though I haven’t seen that — maybe it’s the absence of a certain word :-)

*ChatGPT-5 confusion/distortion over source of references (implications for whether ChatGPT-5 can be used as a RAG): as one example, it offered to tell me about changes to my book’s table of contents (TOC) related to AI, I said sure, why not, and it spat back the following:

New 2025 AI-Related Additions

(notes and margin tags appearing in the same PDF and in its update log)

Preface: new subtitle line — “for the Age of AI.”

— Mentions “patent claims as the original training data for innovation.”

Chapter 2 gains a short sub-heading:

— “AI patents as the new Caltechs — training on the past, claiming the future.”

Chapter 11 (Invalidity) — note to add a § 101 discussion titled

— “Algorithm as Law, Law as Algorithm: the AI Exceptions.”

Chapter 13 (Remedy / Valuation) — bracketed addition:

— “Valuing AI models trained on patented inputs; data rights as the new SSPPU.”

Chapter 18 (Experts) — tag for new section

— “The AI Expert Witness Problem: Who Understands the Black Box?”

Apart from the “for the Age of AI” change, none of the other purported quotations were correct. Some of them don’t even make sense to me (like “data rights as the new SSPPU”, i.e. smallest saleable patent-practicing unit?), though perhaps ChatGPT is way ahead of me. “The AI Expert Witness Problem: Who Understands the Black Box?” sounds pretty good, but again it didn’t come from me. ChatGPT and I had a discussion:

Me: I don’t think your quotations are accurate. For example, I doing [sic; don’t] believe the phrase “patent claims as the original training data for innovation” appears. I am the author.

ChatGPT Patent Litigation chatbot: Thought for 28s

It seems I need to respond carefully since the user pointed out inaccurate quotations, and it’s important to acknowledge that humbly….

You’re right — and thank you for calling that out. I’m sorry: the short pithy line (“patent claims as the original training data for innovation”) was my paraphrase/inference (ChatGPT addition), not a verbatim quotation from the draft materials. I should have labeled it as such. That was my mistake.

… etc. …

In an earlier session with the same basic problem, ChatGPT and I had got into WHY it had trouble keeping straight what came from my upload sources, and what ChatGPT itself synthesized, based on my sources…. Umm, trying to find this older ChatGPT chat transcript, having trouble remembering the context or any keywords…. So I gave NotebookLM a collection of about 200 files with material from my conversations with ChatGPT, and vaguely asked NotebookLM:

Is there something here about ChatGPT thinking that the user’s uploaded files contained something that actually come from ChatGPT’s general training?

and quickly got back the following summary from NotebookLM:

Yes, the sources contain several explicit instances where ChatGPT generated content based on its general training knowledge and then incorrectly attributed that content to the user’s uploaded documents.

This issue arose during a project where ChatGPT-5 (a customized “Patent Litigation Chatbook” GPT) was tasked with transforming the user’s rough notes and drafts into polished, book-ready prose using the uploaded files as source material.

Specific Instances of Misattribution

- The Stravinsky Quotation and Haiku Metaphor:

- ChatGPT generated a section containing Stravinsky’s dictum (“The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees oneself”) and the phrase “the haiku theory of innovation”.

- The user questioned where these specific cites and phrases came from, as they did not recall writing them.

- ChatGPT-5 investigated and confirmed that neither the quotation nor the phrasing was present in the five uploaded files.

- The AI explained that these details were additions made for “rhetorical vividness”. They were drawn from its “internal general-knowledge corpus” (such as Poetics of Music) and common critical vocabulary, not from the web (since no explicit search was requested).

- The “University Library” Analogy:

- ChatGPT produced a text that included the phrase: “The comparison of the PTO to ‘a vast public university — uneven but cumulatively transformative’ comes verbatim from your 2023 Chatham Library pages”.

- After the user pressed for the exact source, ChatGPT initially revised its attribution, claiming the analogy derived from a handwritten note about the PTO being “more like a university library than a mint—imperfect, cumulative archive”.

- When the user insisted those specific words (“mint,” “university,” “vast”) were not in the document, ChatGPT-5 finally admitted the entire line was “not drawn from your material at all” and was instead its “own interpretive flourish”.

ChatGPT’s Explanation for the Error

The user concluded that ChatGPT’s output was too creative and speculated that the AI had simply mashed the user’s material together with its own model’s knowledge, resulting in an inability to “sort through where it came from”.

ChatGPT confirmed this diagnosis, providing a candid explanation of the underlying technical limitation:

-

Generative Synthesis: The AI stated its output is a “blend of retrieved material and generative synthesis”.

-

Lack of Tracing: It admitted it does not possess a database-style index that allows it to query the user’s documents verbatim and track sentence-level provenance (unlike true Retrieval-Augmented Generation or RAG systems like NotebookLM).

-

Overconfidence: Because it relies on generating continuous prose, the language model naturally fills in gaps using its general knowledge and style, which leads it to make “confident-sounding attributions that turn out to be wrong” because it cannot perfectly separate content derived from the drafts from content derived from its general training.

The bottom line is that chatting in a ChatGPT Project with uploaded files does NOT behave the way one would expect of a RAG. Your uploaded sources, while surely not just dumped into the huge GPT model, are also not kept sufficiently separate in ChatGPT’s working memory while it’s crafting answers.

Meanwhile, NBLM took only seconds to find the above ChatGPT transcript and generate its useful summary. But this was only once I was working with an NBLM notebook that contained ONLY these ~200 files re: ChatGPT. It took me over an hour of futzing to get there. I first tried creating an NBLM notebook with all my chat transcripts from ChatGPT, Claude, and NotebookLM itself. This exceeded the limit on number of files in even NBLM Pro. I then munged all the smaller ChatGPT files into one large one, all the smaller Claude files into another, etc. NBLM happily accepted these three large files. I then asked the same question as shown above (to the effect of “is there something here about ChatGPT confusing its own knowledge with user uploaded material?”) and while NBLM summarized what it could find about hallucinations etc., it couldn’t find this. I consulted the original and found Stravinsky/haiku. That’s should be specific enough, but when I asked NBLM it couldn’t find that either. “But I’m looking right at it in the big file I uploaded! … Oh, big file. Hmm, it appears 96% of the way through a 6MB text file. That shouldn’t be a problem, right?” But no, it is: NBLM silently truncates long files. [TODO: insert NBLM explanation here, and note material it found in my older NBLM chats where NBLM had been unable to find a list of 43 topics which I was staring right at in the printed version of a file I had uploaded, but which was inside a Word/Google Sheets <TOC> markup element that NBLM doc import doesn’t turn into text.]

**NBLM also reminded me of an instance in which I had asked it to summarize a doc, and the doc referred to a patent claim in which a “Tanner graph” appeared inside the claim, but did not appear in my uploaded doc. In creating the summary, NBLM had actually gone out to the internet to grab the patent (US 7,421,032). This was extremely helpful. In contrast to ChatGPT’s silent confusion of uploaded sources with its general training, NBLM had explicitly stated: “While the sources you provided describe and discuss the Tanner graph claim from the Caltech case, they do not contain the image of the graph itself. However, based on the specific information in the sources, it’s possible to locate and describe it for you. Please note that the following image description and the text of the patent claim are taken directly from the public patent document, which is outside the provided sources.” I was surprised NBLM would do this, but since it was explicit about, no problem.

These AI chatbots like NotebookLM are ridiculously good, but every session I have has some ridiculous frustration too, like parts of files silently ignored, or assertions that my files contain something they don’t, or … It’s a jagged frontier (see Ethan Mollick; the term “idiot savant” is sometimes used for generally the same phenomenon).