The title of this page says “critique,” and for sure, below I frequently criticize and quibble with the video that Google NotebookLM (NBLM) generated based on hundreds of pages and rough drafts and notes for my forthcoming Patent Litigation book, but I ought to start by saying how shockingly good a job NBLM does with a difficult task. My initial and subsequent reactions when I first watched this video were similar to those that Ezra Klein and Ethan Mollick have recently expressed towards GPT-5. The abilities of LLMs like NBLM are awesome and shocking. All criticisms and complaints below should be taken in that context.

Here is the video, which you can watch while reading the commented transcript below:

This was my second try at an NBLM-generated video based on my Patent Litigation book material. The first time, I simply clicked the “Video” button in NBLM, without any further instruction. The resulting video focused on the $1.1B Caltech vs. Apple/Broadcom case from the book’s planned ch.1 — which would have been fine, but NBLM got enough of the slides wrong (showing material from an entirely different patent), that I decided to ask again, this time with an explicit prompt (clicking the pencil icon in the NBLM Studio “Video” button, before pressing the Video button itself):

“Do NOT focus on the $1.1B CalTech/Apple/Broadcom case.

If you want to focus on a specific case, use the facade server example instead.

Focus on patent claims, limitations, and claim charts.

Also try to focus on how litigation fits into the overall patent system, and the system’s goal of incentivizing invention. How does something low-level like claim charts on the one hand relate to the grand Constitutional goal of ‘promoting progress of science and the useful arts’ on the other hand?”

[I’ve inserted some screenshots of slides into the transcript below. Per Google AI’s suggestion, I used ffmpeg, but (even with further Google AI help with the ffmpeg cmdline) it missed a lot. I then did a sloppy job of hand-extracting relevant slides from the video; I’ll try to fix. I had a bunch of small difficulties with the mechanics of assembling this web page, including getting a text transcript of the video (I had to download the NBLM-generated .mp4 file, then re-uploaded it as an NBLM “Source” file, whereupon NBLM spit out the text). Ideally an AI assistant would just do this sort of thing for me. Perhaps ChatGPT-5 could have done all this for me, and I should have tried a little harder before doing a lot of this manually.]

Commented Transcript

OK. So when you hear the words patent litigation, what comes to mind? Probably like stuffy courtrooms, right, mountains of paperwork, lawyers speaking in jargon. But what if I told you that it’s actually this super high stakes system, a battlefield, really, that’s designed to be an engine for innovation? [It would have been good if the video asked, right here up front, and not merely as a rhetorical question, which this system works as designed. The whole conclusion of the video gets into this, but ideally it would have signaled this at the start.]

We’re going to dive in and connect the dots, see how these massive multi $1,000,000 fights over the tiniest technical details, actually link all the way back to one of the founding ideals of the United States. It’s a wild ride, and believe it or not, it all starts right here in the US Constitution. Now, this isn’t just some dry legalese. This is the mission statement. The whole reason the patent system even exists. [Perhaps ought to specify “US patent system”, though the same basic idea goes all the way back to the Venice 1474 system (quoted e.g. here): “Now, if provision were made for the works and devices discovered by such persons, so that others who may see them could not build them . . . more men would apply their genius, would discover, and would build devices of great utility and benefit to our commonwealth.”]

The goal was never just about giving someone a trophy for a cool invention. Nope, the real goal is to use that reward, this temporary exclusive right as a tool, a catalyst to get everybody else to innovate even more. It’s all about pushing future progress. The patent itself is just the means to a much bigger end, so that really is the $1,000,000 question isn’t it? [“everybody else”: reading or listening to something I didn’t write, but based closely on notes I did write, is an odd experience, and an opportunity to riff on whether what I was trying out in my notes actually works. My notes use the silly phrase “everybody into the pool”, for the idea that we want the patent system (and IP generally) to pull in lots of people who otherwise wouldn’t contribute in this way. This most obviously includes women and minorities. Don’t we want huge number of people participating in trying (even if unsuccessfully) to get patents, if nothing else at least pouring more into the prior-art database? Don’t we want to actively encourage George Washington Carver as well as Luther Burbank? Even if one assumes many will never be granted, and assume (because more likely pro se?) a higher % of eccentric patent applications. And sure, established inventors may not want the queue consumed with “riff-raff,” but at any rate the “everybody else” suggests that what might once have been called DEI/diversity is actually a core purpose of a patent system. Even under Trump, there remain hints of this at the PTO (PTO diversity info). See also von Hippel, Democratizing Innovation, and Khan, Democratization of Invention: Patents and Copyrights in American Economic Development, 1790-1920.]

Or well multi $1,000,000 question, how on Earth do you get from this big, beautiful 18th century idea about promoting progress all the way down to a modern courtroom fight where everything and I mean everything, can depend on the definition of a single word.

That’s the puzzle we’re going to piece together today. We’re going from the 30,000 foot constitutional view right down into the trenches.

All right, first stop. It all begins with this fundamental deal, this trade off. That’s at the absolute core of every patent, you can think of it as the innovation bargain.

So here’s the deal. Imagine you’re an inventor. You’ve got this brilliant new thing. You have a choice. You could, you know, keep it a secret, like the Coke formula, and just hope nobody ever figures it out. Or you can make a bargain with the public. You agree to publish exactly how your invention works, down to the last detail. You give away the recipe, and in exchange for that disclosure, society gives you something huge, a temporary exclusive, right? And what that really means is the right to sue anybody who copies you. So you give up your secret and for a limited time you get a government backed right to stop copycats. That’s the trade. [Not quite down to the last detail. Give away the recipe? Only sort of. Sure, a brief video is going to over-simplify things. And sure, the actual operation is a little confusing: a patentee gives away (“dedicates to the public“) everything EXCEPT what is in the patent claim. It would be nice to be able to edit these NBLM videos (or even better, submit a file like this critique, and have NBLM make the corrections itself). Maybe with Google Vids? NBLM provides audio Interactive Mode, but not yet for video (and I have not yet successfully made corrections using audio interactive mode). The phrase “anybody who copies you” would be another opportunity for engaging with this video: patents unlike copyright don’t require copying; accidental infringement (“reinventing the wheel”, in a sense) is still infringement — the video makes this clear later. Probably too much to expect that level of consistency.]

OK, So what exactly does that exclusive right cover? This is super important. It doesn’t cover the entire product or just the general idea. It only covers what is spelled out in the patents claims.

The land deed analogy is honestly perfect. Think about it, a deed to a piece of property doesn’t describe every single flower and blade of grass. What it does is draw the exact legal boundaries. It says: This is my land and that is your land. That’s what a patent claim does for an invention. It draws the line in the sand. [The flower/grass analogy is good. NBLM came up with this; it’s not in my notes. As for “and that is your land,” actually patents are often not so clear on what doesn’t infringe. My notes get into “what’s-in or what’s-out” issues (you can ask the Patent Litigation chatbook “Do the notes discuss issues of “what’s-in vs. what’s-out” in a patent claim? In particular, anything about whether patent claims provide guidance on what does NOT infringe?”), and note this is one important feature of negative limitations such as “without opening network ports” covered later in the video.]

So if the claims are the property lines, let’s zoom in and look at the anatomy of the invention itself, because this is where the fights really happen.

You can pretty much forget about everything else in the patent, the abstract, the cool drawings, the title on the front. It’s all just context. The claims are what we call the business end of the patent. This is the only part that’s legally enforceable. Seriously. Every single patent lawsuit, every single legal battle comes down to arguing over the precise meaning of the words written right there in the claims. [“pretty much forget about” is a serious exaggeration, but what do you want in a 9 minute presentation? As for “what we call the business end of the patent”, I don’t think that’s a standard way of referring to the claims, though it’s in my notes. As Google AI explains, “In the context of film noir, ‘the business end’ refers to the menacing, threatening side of a gun.” I got the idea of applying to something more prosaic from a Garrison Keillor story with a noir-style grants administrator: “looking at the business end of an air conditioner”.]

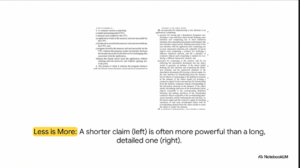

And here’s where things get kind of weird and counterintuitive. When it comes to patent claims, less is almost always more. You think more detail is better, right? Wrong. The shorter, broader claim on the left is way more powerful. It’s like having a claim to a vehicle with wheels versus a claim to a red 4 door sedan with a V6 engine and leather seats.

The first one covers cars, trucks, bikes, skateboards, you name it. It’s much easier for someone to accidentally trespass on that property. [The short-vs.-long claims in the slide come from my notes, but NBLM came up with the vehicle analogy. Note “accidentally trespass”: that’s a good corrective to the earlier “anybody who copies you” error.]

But and this is a big but, it’s also riskier for the patent owner because it’s more likely that someone somewhere already invented a vehicle with wheels. It’s a balancing act. [Should explicitly note that if “someone somewhere already invented” what you claim, and if that can be found in the prior art, that would invalidate your claim. So while patentees want to go as broad as possible to catch more infringers, they also want to go as narrow as necessary to avoid prior art. You can ask the Patent Litigation chatbook, “What’s the book say about Thing Big and Think Small at the same time?”]

So how do these claims actually work? Well, you can break them down. Each claim is basically a sentence, and that sentence is made-up of individual pieces called limitations. The best way to think of it is like a recipe or a checklist for someone to be guilty of infringement. Their product has to have each and every single thing on that checklist, not most of them. All of them. [This would be a good place to explicitly call out the “All-Elements Rule.” Note that “guilty” isn’t the right word: patent infringement is a civil, not criminal matter.]

If they’re missing even one tiny ingredient, just one limitation, then boom, no infringement. It’s an all or nothing game. [Though there might be something that is the equivalent of the the missing limitation. you can ask the chatbook about the Doctrine of Equivalence (DoE), the function/way/result (FWR) test, and known interchangeability.]

OK, so we’ve got this all or nothing checklist. How does that actually play out in a real lawsuit? Let’s step onto the battlefield. The claim chart battlefield.

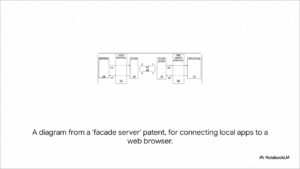

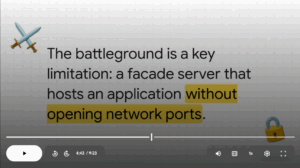

All right, to make this real, let’s look at an actual example. This diagram is from a patent for something called a facade server. It’s a clever little invention. The whole idea is to build a sort of digital bridge, something that lets an old school program running on your computer talk to a modern web browser, but without actually having to connect to the whole Internet. [The patent is US 7,472,398 — “the whole Internet” is a bit confusing; the patent claim itself requires “without utilizing network protocols and without opening network ports”.]

Now remember, the lawsuit isn’t about the general idea of a [program/UI] bridge. It’s about the nitty gritty. Like this specific limitation right here. Look how precise it is. It’s not just a server, it’s a server that has to do its job without using network protocols and without opening network ports. Those withouts are everything. They’re called negative limitations, and they’re usually put in there to prove to the Patent Office that this invention is different from anything that came before it, and you better believe those words become the heart of the legal fight. [More unnecessary NBLM exaggerations: “are everything”, “those words become the heart”. Often true, for sure, but this almost makes it sound inherent. And a “kicker” to a claim, distinguishing it from prior art, is generally signaled with the word “wherein” (e.g. in ‘398 claim 1: “wherein the facade server hosts the application without utilizing network protocols and without opening network ports”), without necessarily taking negative “without” form. You can ask the chatbook about the Point of Novelty (PON). Hmm, I wish there were a way to create a URL for a shared NotebookLM notebook, with a prompt specified in the URL, as I’ve been doing here with Google AI URLs: ask Google AI about Point of Novelty (PON).]

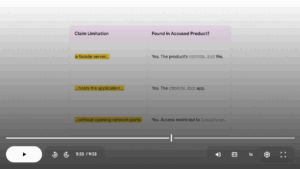

And this is what that fight looks like on paper. It’s called a claim chart, and it is the central document in almost every patent case. It’s super methodical. The patent owner takes their checklist, their limitations on the left, and on the right, they have to point to the exact spot in the other guy’s product where that feature exists. [Definitely the central doc for the technical side of a patent case, but probably not to those working at other levels, such as monetary damages.]

See, they’re saying your SERVER.EXE file is the facade server for my claim. Your CMDRUN.EXE is the application from my claim. They have to map every single piece.

And because these claims can get insanely complicated, lawyers and experts will literally draw them out like this. It’s a way to get out of the weeds of the legal text and just visualize how the invention is supposed to work. How does this piece connect to that piece? It basically turns a dense paragraph of legalese into a simple blueprint, a map of the invention that you can actually understand. [I’m not sure the following back-of-the-envelope drawing has the importance NBLM seems to attribute to it.]

OK, so we’ve been deep in the weeds, looking at these tiny details, but now we need to zoom way out because here’s the most important thing to get. This messy, argumentative, adversarial process [of patent litigation]. It’s not a bug, it’s not a sign the [patent] system is broken, it is the system. That’s how it’s designed to work, right? A patent isn’t a magic shield.

You can hang that fancy certificate on your wall, but it’s basically worthless by itself. There are no patent police who go out and arrest people for infringing. A patent is only as valuable as the owner’s willingness and ability to sue someone in court. [“basically worthless by itself” is another over-statement, but in this case I think it accurately reflects some of what I’ve written. On “no patent police who go out and arrest people”: “no patent police” is important and comes from my notes: pursuing infringers is DIY, albeit of course with the patent system as government backing. Robert Merges refers to this as giving patent owners a “dollop of state power“. But the “arrest people” part doesn’t make sense because, as noted earlier re: “guilty”, patent infringement is civil, not criminal. Some patent enthusiasts want it to be a criminal offense (in line with some plaintiff trial lawyers telling the jury about “theft” and “stealing”), but I don’t think they’ve thought this through: do they really want patent infringement to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt (BRD) rather than requiring only preponderance of the evidence?]

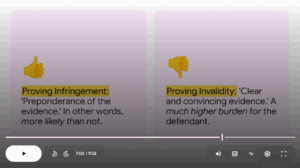

That’s it. The entire patent world, from how inventors write their claims to how companies decide to license technology. It all happens in the shadow of one thing. The threat of a lawsuit. And once you get to court, the system is designed with a bit of a home field advantage for the patent owner. See, once the US Patent Office grants a patent, it’s presumed to be legit. [A presumption, but importantly a rebuttable presumption, if clear and convincing evidence (a higher bar than preponderance of the evidence).]

So for the patent owner to prove you’re infringing, they just have to convince a jury that it’s more likely than not, basically a 51% chance. But if you’re the one being sued and you want to argue, the patent should never have been granted in the 1st place, you have a much, much higher hill to climb. You need clear and convincing evidence. The patent holder definitely has the upper hand starting out.

But that advantage is a total double edged sword. Going to court is the ultimate test. It’s like putting your patent in a crucible, and this is where the stakes get incredibly high. If you sue someone and you lose and the court decides your patent is invalid, it’s not just that you lose that one case. Your patent is dead, wiped off the books forever. For everyone, it’s a massive gamble. You have to use it, but you might just lose it. [NBLM actually understood the book’s “use it AND lose it” point; many a human editor would quickly change this to the usual phrase “use it or lose it,” without considering what’s being said here — that the very use of a patent can endanger the patent). While the video hedges enough with “possibly” and “might just lose it,” the whole bit about how if “court decides your patent is invalid, it’s not just that you lose that one case. Your patent is dead, wiped off the books forever”, is much too emphatic, and over-simplifies issues with res judicata, collateral estoppel, and non-mutual collateral estoppel: does invalidity in P v. D1 necessarily mean invalidity in P v. D2? See e.g. USAA v. Wells Fargo, and USAA v. PNC.]

And that brings us right back to where we started, back to that grand idea in the Constitution. So how does all of this this conflict, this complexity, this high stakes gambling, how does any of it actually help promote the progress of science [and the useful arts]

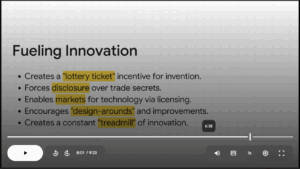

Well, the theory is that it works in a few key ways. For one, the possibility of a huge payout from a lawsuit acts like a lottery ticket, encouraging people to take big risks on wild new idea.

Second, it forces people to disclose their secrets, creating this massive Public Library of knowledge that anyone can learn from and build upon. It also creates a market for ideas, so you can license or sell your technology. And maybe most importantly, it encourages competitors to get creative instead of just copying, they have to design around the patent, which often leads to even newer, better inventions, it all adds up to this constant treadmill of innovation where you can’t stand still. [“forces” should be “pushes”.

— Interesting that NBLM says “maybe most importantly” for the incentive to design-around.

— “Constant treadmill of innovation where you can’t stand still”: see Joel Mokyr, “Intellectual Property Rights, the Industrial Revolution, and the Beginnings of Modern Economic Growth“.

— “this massive Public Library of knowledge”: this raises the questions, How much in this patent-induced library (earlier patents and published patent applications) would not otherwise exist in academic papers, and To what extent do engineers actually benefit from this patent library in their everyday work outside the patent system? See Lisa Ouelette, “Do Patents Disclose Useful Information?“.]

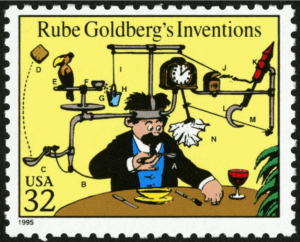

So yeah, it looks messy. It can absolutely feel like one of those crazy convoluted Rube Goldberg machines where a whole lot of stuff has to happen just to flip a switch. But that complicated machine is the engine we’ve built. It’s the process we came up with to do something almost magical: to take a simple idea, turn it into property, and then use that property as the fuel to drive progress forward. [“the fuel” really ought to be “one form of fuel”, since the patent system is not the sole incentive (fuel) for invention, other incentives being government grants/contracts, and industrial policy.

— NBLM has a slide that says “Rube Goldberg,” but of course we want a slide that SHOWS a Rube Goldberg device. Presumably NBLM has copyright concerns about dropping in anything other than clip art. Asking Google AI, “Is Rube Goldberg out of copyright?“: “No, not entirely. While Rube Goldberg’s specific cartoons and the original designs he created are out of copyright, the term ‘Rube Goldberg’ and the concept of the machine are protected as a registered trademark by Rube Goldberg Inc.”. The slide could show the US Rube Goldberg postage stamp:

or the equivalent Heath Robinson (Google AI: “Yes, many William Heath Robinson drawings are out of copyright, especially in the United States, because they were published before January 1, 1930, and the author died in 1944”), like this folding garden:

But you can see why Google doesn’t want to have to hash out image copyright issues every time someone asks for an NBLM video, even though the videos clearly suffer from their absence. This generally includes even images appearing in patents, such as the Tanner graph claim in one of the book’s key examples, Caltech vs. Apple/Broadcom.]

And that really leaves us with the big question, doesn’t it? Is this incredibly complex, ridiculously expensive, and sometimes brutal system a necessary evil? A treadmill that we have to keep running on to keep technology moving forward? Or is it more like a convoluted lottery, one that hands out a few giant jackpots but mostly just gets in the way of real innovation? And the truth is people are fighting about that every single day. The real answer is probably somewhere in the middle.